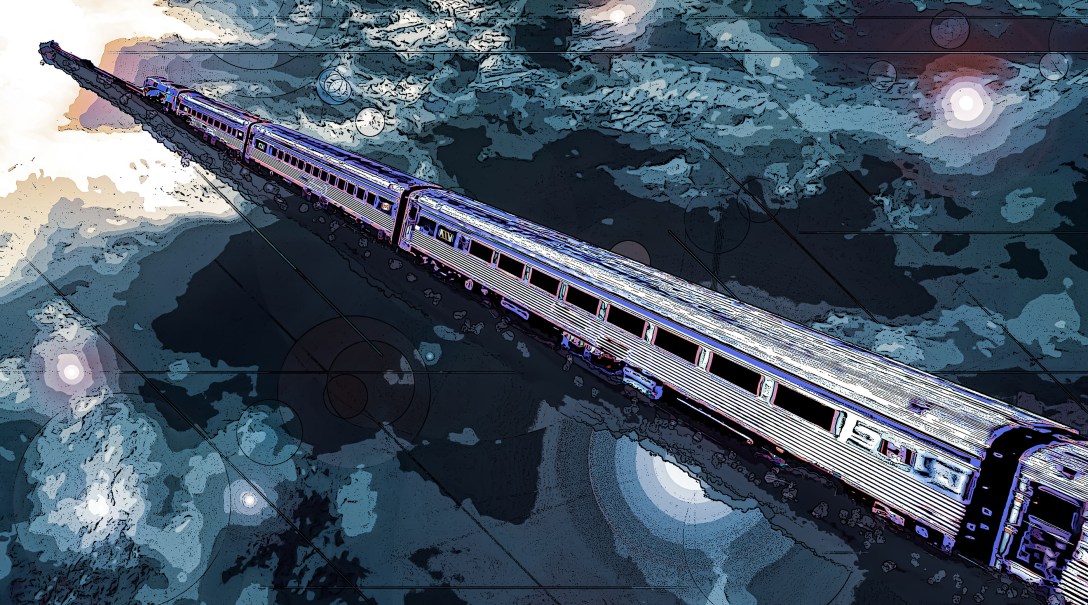

Sometimes, it’s difficult not to see your life rolling out in front of you, predetermined on a pair of tracks. Like a train, clanking slowly, monotonously through the backsides of countless towns.

Each of these towns could be exactly the same, except for minor differences, some you might notice, some you might not. In some, they might grill the hotdogs at their foodstands, and in others, boil them. But most of those changes, no one really cares about, or cares to notice. It’s just another trip on your endless ride to nowhere.

But people aren’t looking close enough. Pay attention, and you’ll notice you’d be surprised to find a teller with a third eye blinking in the middle of his forehead, like the man from the Twilight Zone. If you were to engage her in conversation, you might find that the woman in curlers sitting next to you chemically produces meat patties for sustainable colonization of Mars. Modern life courts the bizarre, makes love to the surreal. It’s simply that we, in our infinite wisdom, have developed habits, calendars, and schedules, to make everything seem copacetic. This, in turn, keeps us from blowing our brains out the first time we see tentacle-faced freak flipping burgers.

It’s not prejudice, exactly, but the human mind can only believe in so much. Trust me when I say the TFFs don’t like it any more than you do.

Some people find an alternative, exit at one stop or another, and dig deep into their lives. Who cares, after all, if there are clouds of floating jellyfish teeming through the air if it’s in a place you call home?

Others, though, rankle at the restriciton. They hop from town to town, serving milkshakes to mantis men one week, then hop two stops down to a place where everyone wears shoes on their hands. They wrestle with the world in an attempt to find somethig more. But, if you see everything as marginally the same, that’s exactly what you’re going out there to find. It’s a Catch-22 that Joseph Heller would be proud of.

Corey Akerdsfeldt had been riding the rails longer than most. He’d worked every conceivable entry-level job you could imagine, cleaning toilets, stocking shelves. He’d even worked as a lifeguard for fish who were trying to learn to swim through the air.

By the time he was thirty and his hairline had started receding, he’d decided it was time to settle down a bit. It didn’t matter where he went, age would catch up with him anyway, and he might as well accumulate a little wealth. Maybe find someone to live with. Get a hobby.

So, he found himself a job working in logistical finance, whatever that was, snagged a cubicle by a window, and began the long, dry process of setting up a life. He took up cycling arbitrarily and met a young woman named Barbara. She told him on their second date that she liked his receding hairline. In this dimension, people saw it as a sign of virility.

Later that night, when she first unboxed him, she squealed when she first noticed that one of his nipples was higher than the other and that they were both different colors. She’d kissed them, one after another, and wondered aloud how she’d gone so long without being with anybody, so many years without witnessing another’s physical imperfections. Nakedness, to her, was no metaphor. A person’s nakedness revealed to her some degree of truth. It was like reading a book, where each dimple, each scar, and line, was another chapter in the life of a thing so often hidden behind its bindings.

They made love like a locomotive that night, their mutual climax as assured as the times posted on each stop.

Still, you couldn’t say Corey was happy, even when, most nights he got to play the big spoon to Barbara’s bones. Work pulled at him. He spent most of his time avoiding his supervisor, a large fat man with a manatee mustache and a penchant for calling him Daryl, though for what reason Corey could never understand. The other half of the time, he organized and re-organized spreadsheets, answering the occasional email with one or two-word answers.

The boredom of it all sickened him. Every day there was a constant fight to keep it back, to fill his mind with something else than the fact that he was still on his own sort of train, still allowing life to take him by the neck and drag him wherever it felt like. Everything in his life was arbitrary and lacked meaning. He was constantly half a second away from remembering his absolute powerlessness and made him tremble.

One afternoon Barbara pulled into the parking lot of his apartment building while Corey was raking up the globs of star jelly that had fallen on his front lawn the night before. She helped him finish piling the things into sagging plastic bags and accidentally fell into one of the piles, soaking the right leg of her blue jeans all the way up to her thigh. He tried to help her get up, but when she took his hand, she pulled him down into a fateful of mud and jelly.

“Oh, fuck you,” he said, shaking with laughter.

“That’s the idea.”

They wrestled down there in the jelly, in front of everyone, until their clothes were soaked through.

Afterward, they took a shower together, and Barbara ordered pizza while he mixed them both a drink.

“Holy shit, marry me already,” she laughed, as he brought her a negroni with a lemon rind twist hanging off its edge. “This is the fanciest thing I’ve ever seen!”

Together, they watched the sunset off of his balcony, ate the pizza, and had another drink. Then, they curled up into each other on the couch and put on Blade Runner.

By the time they got to the part where Priss was introducing Rutger Haur’s character to J.F. Sebastian, Corey had reached his fourth drink. After the last one, he’d stopped bothering with the mixing, and poured himself a finger or three of Evan Williams. When he returned, Barbara lay her head across his lap and mumbled something about unicorns. Her breathing slowed, and she started to snore lightly.

As Corey drank, he felt his body loosen, his mind wandered off into the night, past Deckard and Gage, past his television, and out into his memory. The old fear crept back into the shadow of his consciousness, of stasis and growing old. It swarmed his mind until he could no longer see. His heart began beating faster and faster, like a freight train leaving the station.

Looking down at Barbara, he felt contempt enter his heart. In a moment, she became the reason that his life felt so stagnant. It was she, not him, who made the tracks that lead off into the horizon of his life seem so inevitable. It was her he stayed for. But why?

Even as he thought it, he knew it was not her or this place, but himself that he hated. He hated himself for not finding the place that would make him happy, for getting off at this particular stop. He hated himself for getting off at all, and even for not getting off sooner, where things could have ended up better.

He slammed the last of the bourbon and stood up to get another.

As he heard poured another drink, he heard a groggy voice from the other room ask, “The hell was that for?” but he barely registered it. “You’ve gotta treat my head at least as well as an egg, it’s worth more, I hope,” Barbara laughed, looking at him over the couch.

“Sorry, I wasn’t looking where I was going.”

“You’ve had too many of those,” she said, then narrowed her eyes. “You’re upset.”

“I was just thinking about my time on the rails again. Miss them sometimes.”

“Aww, poor baby,” she said, and then, serious now “you know you can leave whenever you want.”

“Where would I go? It’s all the same.”

“That’s in your head, Cor. Not in real life. Everywhere’s special, and so is everyone. Just because you can’t see it doesn’t make that true. ” Behind her, Rutger Hauer’s character was giving the speech about tears in rain. A dove flew slowly out of the frame.

“I’m tired. Let’s just go to bed.”

“Look at me. Look at this face. Don’t you see something, anything worth holding on to?”

“Let’s just go to bed.”

She looked at him for a while, her eyes searching. “Alright.”

Barbara lay awake for hours as Corey clung to her closer than he ever had before, but already she could not feel his touch.

The next couple of weeks saw a change in Corey. He called Barbara less often, and when he did, his voice seemed dull and monotonous. She learned later that he’d quit his job, and stopped shaving.

One day, as she passed the station in her car, she saw him standing there, a suitcase in either hand. He was smiling as a steam locomotive covered in cog wheels floated out of the sky and landed with a whoosh out in front of him.

Barbara did not stop to get out or wave. When she got home, she found a heap of her things and a key to the house that she’d given him. Before she did anything else, she took everything of his that she could find and threw them in the garbage. She deleted every photo that she had of them together. Then, she took out a broom and swept the whole house. The dust billowed and fell like snow in the morning light.

Corey would not be back, and she knew it. But that was alright. Soon, she would adjust and recover. Soon, it would be like he’d never existed at all. And to this place, this station on the twisting black line that is the train between this and then, that, now, and everything in between, perhaps he never had.

Outside, the train whistle blew.