Often, though, experimental artists forget the process. They seek to create art that shocks or impacts their audience, using the tools of experimental artists who came before. But they aren’t actually generating any of these tools. The experiment is gone, replaced by the afterimages of experiments past, endlessly repeated.

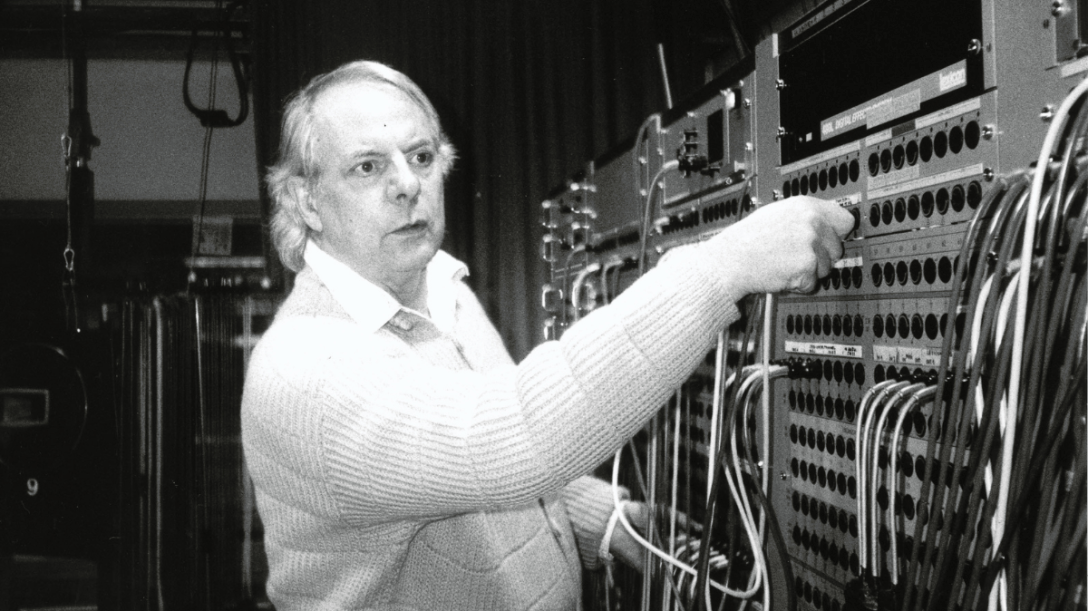

Does this make these pseudo-experiments bad? Not necessarily. Some of the most well-done productions I’ve seen skirt the line between process-based experimentation and just being a cool interpretation of a play. Experimentation does not equal quality, and quality does not equal experimentation. And even if an experiment is well done, that doesn’t mean people will, or should, like it. Edinburgh based avant-garde metal band Thy Catafalaque puts out some of the most interesting and challenging music I can think of, but they’re no Karlheinz Stockhausen, whose musical theories included notions like statistical composition, and polyvalent fields. Stockhausen’s music bleeds complexity, but half the time all this means is that you’re listening to complex noise. Thy Catafalaque still retains a human quality that makes it listenable, while Stockhausen, objectively more experimental, just doesn’t.

Experimentation takes a very long time, and there’s not a whole lot of return on your investment. Just because you’re experimenting doesn’t mean that your work will galvanize the artistic world. You also have to have talent, dedication, and more than a bit of luck to do that. You might just make something bad that no one cares about. Relying entirely on process can make you soar, but just as often it will leave you with your face in the dirt, wondering how and why you got there. An artist has every reason not to make that leap.

But often the experimental label makes an artist or piece self-important in a way that it doesn’t merit. Art that results from experimentation falls prey to this too. Being an experimental artist has somehow come to mean that that you are ever so serious and important, charging your work with a pretentiousness that ruins any legitimate creativity. But by accepting the experiment as a genre rather than a process, experimental art work ends up becoming the artistic equivalent of your sister’s goth phase in middle school, constantly trying to appear darker and more extreme, when really, she’s just having a hard time fitting in, and can’t deal with your mom’s new boyfriend. Subconsciously aware that it has not affected the revolution in human thought as it has promised since the 19th century, experimental artists use the same tools that worked fifty years ago, but uses them harder, in an artistic temper-tantrum that convinces no one, but comforts the user into believing that they, alone, are doing something radical.

Don’t get me wrong, experimentation is extremely important, capturing the spirit of the age in its roundabout processes better than any documentary. But it still comes from the same place as any other artwork: human experience. A poet like Robert Frost, who uses traditional metrical devices and rhyme schemes, attempts to express the same humanity as Nathaniel Mackey, who shapes language and meter to the service of his work’s musicality. Experience and humanity actually drive innovation, are the chaotic factors that give art the spark of life. When the genre of experimental art forgets this, it paints itself into a corner. The past’s innovations calcify into axiom. Afraid that letting in any sense of life will open them to criticisms of being realists, they effectively create artistic corpses, beautiful to look at, but with no movement in them.