Author: Dan Christmann

TheGamer List Samples

These are some of my favorite articles I’ve written at The Gamer thus far. Come for gaming information, stay for ridiculous jokes about being beaten up by crabs.

https://www.thegamer.com/average-rpgs-amazing-endings/

https://www.thegamer.com/jotun-beginner-tips-know-before-playing/

https://www.thegamer.com/most-convoluted-side-quests-in-elden-ring/

Cibo: Fighting Hate With Art

A Cloud of Unknowing: Madison Square and the Nature of Environmental Justice

Biodigestion and the Greening of West Michigan

WMEAC Summer Camps: Science, Community, and Meatloaf

WEMAC Blog: Preventing Food Waste in Grocery Stores

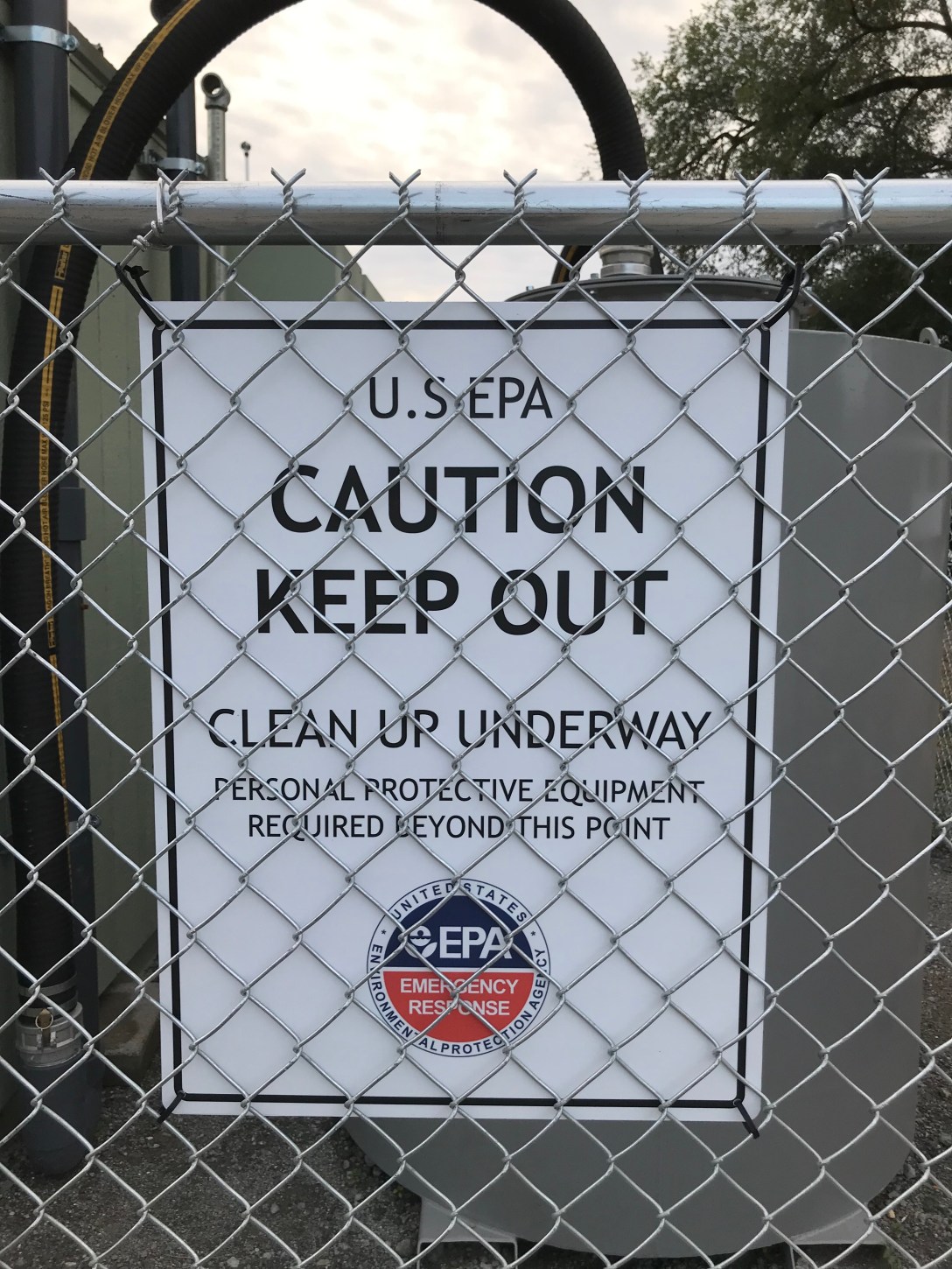

Legacy Contamination: A Short Informational Primer

Origially Published in The Grand Haven Tribune in 2019

Finding that legacy pollution on your property is a bit like realizing your house was built on an abandoned burial ground in a bad horror movie: both release potentially harmful, seemingly invisible influences on your life that everyone is too embarrassed to tell you about until after the haunting starts.

And, like desecrating the grave of a vengeful spirit, you will be the one that reaps the consequences, even if you didn’t intend it.

This is what makes legacy pollution — of which probably the most infamous right now is PFAS — so terrifying. These are chemicals all around us that we weren’t aware of, and so could affect any of us. In many cases, manufacturers didn’t even know they were harmful until after we put them into the environment.

Michigan has an unfortunate history with this sort of thing, from the contaminated air that sweeps off Zug Island, to the dioxin still embedded in Tittabawassee River sediment, courtesy of Dow Chemical.

The issue came to the West Michigan Environmental Action Council’s attention when we were investigating the cleanup of a vapor intrusion site in southeast Grand Rapids in 2016. There, carcinogenic chemicals known as trichloroethylene (TCE) and perchloroethylene (PCE) were leaking up into the air from an old dry cleaner. The state had known about the contamination for a while, but we were just beginning to realize that these chemicals could leak into the air in a vaporized form.

Only a year before, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency had changed their standards as to how much of these chemicals were safe to be around. As a result, the site in southeast Grand Rapids, as well as 4,200 others, became pollution hotspots over time.

The unfortunate fact of the matter is that the way we use and discover chemicals often lags behind our understanding of what they do to us. That’s what makes this sort of thing possible: These were miracle chemicals that solved an important need. We didn’t have any reason not to use them. In the case of the southeast Grand Rapids site, there’s not even anyone to blame anymore. The dry cleaner stopped operation in the 1990s.

This makes legacy pollution tricky from a legal standpoint. According to parts 201 and 213 of Michigan’s Natural Resources and Environmental Act, owners and operators are the ones responsible for testing the level of contaminants on their property. However, this requires that you know about contamination on your property. If you don’t, the law doesn’t exactly make clear what happens next. In a lot of these cases, the Michigan Department of Environment, Great Lakes and Energy (EGLE) keeps records of historical contamination sites, but because of the way the law works, it’s not technically their responsibility to inform you.

This is the Catch 22 of legacy pollution: We’re expected to test for it when we don’t know that there’s anything to test. If we go with an earlier metaphor, that’s like holding you responsible for finding the cursed archeological site under your house when you didn’t even know people around here bury their dead. You’re a software programmer from Bangalore.

Fortunately, EGLE and the EPA will intervene like in the case of high-profile legacy pollutants, such as the PFAS at Robinson Elementary School. But there’s only so much that these agencies can do. There isn’t enough funding to test TCE and PCE levels in every former dry cleaner. They have to pick and choose which potential sites seem like they could do the most harm.

Sometimes mistakes get made. Sometimes harmful substances leak into our lives.

In those cases, you are the only one who can find out. You are the only one who can draw attention to it. And you are the one responsible for setting it right.

If you’re concerned that a place you work or live in might have lingering pollution, EGLE keeps a database of potential sites and a map tool. They also host a series of webinars, along with in-person training on a variety of topics. The EPA also recently launched a chemical review status tracker that can help you pinpoint potential sites.

Making Experimental Art: A Guide for the Perplexed (Pt. 4)

The fact that experimental art calcifies into sameness should not come as a surprise, since it is the general trend of art in general since the enlightenment. Ever since art and utility became separated and art for the sake of art became the norm, it has gained a magical quality that separates it from its processes and the experience of the people who create it. the American philosopher John Dewey, in his 1934 book Art as Experience, puts it better than I ever could when he writes, “When artistic objects are separated from both conditions of origin and operation in experience, a wall is built around them that renders almost opaque their general significance, with which esthetic theory deals. Art is remitted to a separate realm, where it is cut off from that association with the materials and aims of every other form of human effort, undergoing, and achievement.”

Put another way, when a piece of art is put into a museum, a poet made national laureate, or a piece of literature is taught in high-school English, it becomes a holy relic that we either reverie or despise because we sense it may not actually be a piece of the true cross. And, like many relics, true origin matters very little. Its presence in the church has made it holy.

New forms of experimental art often represent an attempt to escape this artistic canonization, while containing within them the seeds of their own failure. Take, for example, Marcel Duchamp’s Fountain, where the artist famously submitted a urinal signed “R. Mutt” for display at the inaugural exhibition of the society of independent artists in 1917. The piece intentionally subverted the idea of fine art, both degrading the stuffy gallery culture of the time and elevating everyday objects. Art, Duchamp asserted, is what we perceive as art. It is defined by its arbitrary presence in a building designed for art.

Instead of deconstructing the museum, however, Duchamp only added to what museums would consider displaying. The museum itself canonized the radical gesture of diverting from gallery culture, making it just as inaccessible to everyday people as any rare Rembrandt, perhaps more so, since to understand Fountain, a person needs to be well versed in the artistic climate of the early 1900’s. That which a person cannot understand, but which is held in esteem by experts, increases its mystery and therefore its status as art. We begin to identify art as something defined by its lack of comprehensibility. By protesting arts elevated place, Duchamp contributed to art’s continued elevation.

By slow degrees, experimental art as a genre became, at least in the eyes of experimental artists, the holy of holy’s, not just the fingerbone of a hallowed saint, but the saint himself, reclothed in flesh and handing out miracles. It separated itself even farther from a thing which, by its very nature, already seems separate. Caught in its own self-referential cycle, it forgets where it comes from entirely, its raison de entre to perpetuate its own inscrutable position. The only way to free experimental art from its self-imposed exile is to remind its makers that, as Dewey writes, “Mountain peaks do not float unsupported; they do not even just rest upon the earth. They are the earth, in one of its manifest operations.”

Making Experimental Art: A Guide for the Perplexed (Pt.3)

Often, though, experimental artists forget the process. They seek to create art that shocks or impacts their audience, using the tools of experimental artists who came before. But they aren’t actually generating any of these tools. The experiment is gone, replaced by the afterimages of experiments past, endlessly repeated.

Does this make these pseudo-experiments bad? Not necessarily. Some of the most well-done productions I’ve seen skirt the line between process-based experimentation and just being a cool interpretation of a play. Experimentation does not equal quality, and quality does not equal experimentation. And even if an experiment is well done, that doesn’t mean people will, or should, like it. Edinburgh based avant-garde metal band Thy Catafalaque puts out some of the most interesting and challenging music I can think of, but they’re no Karlheinz Stockhausen, whose musical theories included notions like statistical composition, and polyvalent fields. Stockhausen’s music bleeds complexity, but half the time all this means is that you’re listening to complex noise. Thy Catafalaque still retains a human quality that makes it listenable, while Stockhausen, objectively more experimental, just doesn’t.

Experimentation takes a very long time, and there’s not a whole lot of return on your investment. Just because you’re experimenting doesn’t mean that your work will galvanize the artistic world. You also have to have talent, dedication, and more than a bit of luck to do that. You might just make something bad that no one cares about. Relying entirely on process can make you soar, but just as often it will leave you with your face in the dirt, wondering how and why you got there. An artist has every reason not to make that leap.

But often the experimental label makes an artist or piece self-important in a way that it doesn’t merit. Art that results from experimentation falls prey to this too. Being an experimental artist has somehow come to mean that that you are ever so serious and important, charging your work with a pretentiousness that ruins any legitimate creativity. But by accepting the experiment as a genre rather than a process, experimental art work ends up becoming the artistic equivalent of your sister’s goth phase in middle school, constantly trying to appear darker and more extreme, when really, she’s just having a hard time fitting in, and can’t deal with your mom’s new boyfriend. Subconsciously aware that it has not affected the revolution in human thought as it has promised since the 19th century, experimental artists use the same tools that worked fifty years ago, but uses them harder, in an artistic temper-tantrum that convinces no one, but comforts the user into believing that they, alone, are doing something radical.

Don’t get me wrong, experimentation is extremely important, capturing the spirit of the age in its roundabout processes better than any documentary. But it still comes from the same place as any other artwork: human experience. A poet like Robert Frost, who uses traditional metrical devices and rhyme schemes, attempts to express the same humanity as Nathaniel Mackey, who shapes language and meter to the service of his work’s musicality. Experience and humanity actually drive innovation, are the chaotic factors that give art the spark of life. When the genre of experimental art forgets this, it paints itself into a corner. The past’s innovations calcify into axiom. Afraid that letting in any sense of life will open them to criticisms of being realists, they effectively create artistic corpses, beautiful to look at, but with no movement in them.