Edward Albee’s Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? is given to many possible interpretations. Set in a fairly realistic manner, we could take it as a literal confrontation between two couples employed at a small university in the fictional town of New Carthage. However, Virginia Woolf does not fit comfortably within a realistic idiom. The play contains too much excess for the barren life of a naturalistic drama. Bursting at the seams with complexity, heightened language, and characters that seem torn straight from popular magazines of the time, Virginia Woolf cites the conventions of realistic drama without adhering to them. However, it is the final act, the “Exorcism”, which truly breaks the idea that Virginia Woolf is presenting contemporary life. The summoning and sacrifice of Martha and George’s imaginary child seems so laden with symbolism and portent that it ripples backward, altering and at once unmasking the play before our very eyes. Anne Paolucci writes that, “A kind of religious awe pervades the closing minutes of the play; the coming of dawn is the paradoxical symbol of exhaustion and death. The mystery is a dilemma; revelation a trap. The mystical experience is reduced to a pathetic series of monosyllables. […] but in their tragic awareness of the emptiness they have created, Martha and George are redeemed” (62-63). As we engage with Virginia Woolf, we see characters who move from a realm of heightened-yet-mundane life into a realm of the spirit.

However, as far as I am aware, Virginia Woolf continues to be staged as if it were a realistic play. Though I would not advocate abstract staging in all cases, this seems a shame to me; the theatrical equivalent of hiding one’s light under a bushel. As Harold Clurman writes, the play “verges on a certain expressionism,” which, if emphasized, could bring out some of the text’s richness, and elevate some of the plays more interesting elements (79). Many of these elements are, as Paolucci suggests, more ritualistic than realistic. In fact, I would contend that Virginia Woolf does not exist in a realistic idiom of the contemporary world at all. Rather, its characters are ritual participants in a rite of passage as characterized by Arnold Van Gennep and Victor Turner. Occurring during the liminal phase of the ritual, the play displays all of the classical hallmarks that Turner and Gennep outline, each participant stripped of their social status until each reveals their essentially human character. As in Turner, the play also links the catharsis and emotional upheaval that its characters undergo to communitas, the speculative, mystical experience which inspires religion. Rather than being “Aimless… butchery. Pointless,” this ritual logic gives purpose to George and Martha’s codependent and destructive relationship (Virginia Woolf, 193). As people who, at least unconsciously, believe in the possibility of redemption, the characters in Virginia Woolf constantly attack each other not merely to destroy, but so that they might be transformed.

While it may seem unusual at first to compare a piece of contemporary drama to a ritual, traditional theatre from Japan, China, Greece, and medieval Europe all have religious or cultic sources. Like theatre, ritual can be categorized in terms of auditory and gestural semiotics. Some more modern rituals, like the Catholic mass, even have texts that behave like play scripts, with scholars scouring them for what ultimately must be the “correct” interpretation. However, where the two genres differ is in their import in the lives of everyday people. While today drama continues to alter the lives of those who observe it, it does so only rhetorically. It uses the same tools as other communication media, moving us emotionally and intellectually. In contrast, rituals are believed to act directly upon the people who they concern, sometimes changing their lives in a very literal and profound way. Often, Western culture has brushed this aside as stemming from a simplistic belief in magic, but the difference is rather one of worldview. For a modern, secular individual, humanity’s relationship to the world is either one of domination or awe. We have intellectually separated ourselves from the spiritual aspects of the natural world, and so what is natural from what is human. From a ritual perspective, however, natural and artificial interweave in spirituality. What each human does on the earth effects the general cosmos and vice versa. In this belief paradigm, any action a person takes has the potential to perform magic, and anything unexplained might come from an imbalance occurring in the macrocosm. Rituals are merely the specific and repeated versions of magical actions that participants believe have worked before. They are designed to be both extremely utilitarian and extremely logical, to create balance or prevent the world from tilting. The logic, however, originates in a place that only a few sons of the enlightenment would understand.

One of the few nineteenth century scholars to grasp the complexities of ritual practice was Arnold Van Gennep, a French anthropologist most famous for profiling a certain species of ritual: what he identified as rites of passage. These rituals involve changes in concrete social state or location, and include puberty rites, marriage ceremonies, rituals following a death, and even blessings performed upon an individual leaving the sacred area of the tribe. According to Van Gennep, “Such changes of condition do not occur without disturbing the life of society and the individual, and it is the function of rites of passage to reduce their harmful effects. That such changes are regarded as real and important is demonstrated by the recurrence of rites, in important ceremonies among widely differing peoples, enacting death in one condition and resurrection in another ” (13). For participants, these rituals were not mere markers or festivals thrown to celebrate an important occasion, but were meant literally to change a person into something, or someone, else. To comprehend this properly, it is necessary to realize that in many societies where these rites are important, identity functions in culturally specific ways. One’s personhood seems more static than the Western conception, and yet somehow more fluid. It is as if castes or social positions are containers into which individuals flow. A certain process, usually symbolic, is required to remove the liquid personality and contain it again within a recognizable part of the social structure. Thus, a man cannot become a shaman simply because he chooses to. Rather, the process chooses him, transforming him into a new incarnation of himself.

Along with a basic categorization of these rites, Van Gennap identifies three components: smaller rites or sub rites that combine to form a rite of passage. He calls these rites of separation, transition, and incorporation, also identified as the preliminal, liminal, and postliminal phases (Rites of Passage, 11). In his book, The Ritual Process: Structure and Anti-Structure, Victor Turner elaborates that

“The first phase (of separation) compromises symbolic behavior signifying the detachment of the individual or group either from an earlier fixed point in the social structure, from a set of cultural conditions (a “state”) or from both. During the intervening “liminal” period, the characteristics of the ritual subject (the “passenger”) are ambiguous; he passes through a cultural realm that has few or none of the attributes of the past or coming state. In the third phase (reaggregation or reincorporation), the passage is consummated”(98).

Thus, in each rite of passage, a participant is taken away from their community, caused to wander the wilderness, and brought back as a new being.

It is important to note here that not all rites of passage include all three of these phases in their fullness. While Van Gennep, like much early anthropology, is prone to generalization that fails to differentiate sufficiently between the rituals of vastly different cultures, he is cognizant enough to give his model flexibility. Thus “although a complete scheme of rites of passage theoretically includes the preliminal rites (rites of separation), liminal rites (rites of transition), and postliminal rites (rites of incorporation), in specific instances these three types are not always equally important or equally elaborated” (Van Gennep, 11). In certain societies, a rite of passage may consist entirely of incorporative rites, or leave its participants in states of liminality for an extended period of time.

If Virginia Woolf exists as a rite of passage as I contend then it is one composed largely of the liminal phase: it’s participants stranded ambiguously between gaps in the social structure. In the liminal phase, personal identity is destroyed; participants are set outside of social time and prepared for entrance into another. Turner, an anthropologist who worked much with the concept of liminality, describes this process as one which grinds down the personalities in transition, strips them to their essence:

“The neophyte in liminality must be a tabula rasa, a blank slate, on which is inscribed the knowledge and wisdom of the group, in those respects that pertain to the new status. The ordeals and humiliations, often of a grossly physiological character, to which neophytes are submitted, represent partially a destruction of the previous status and partly a tempering of their essence in order to prepare them to cope with their new responsibilities and restrain them in advance from abusing their new privileges. They have to be shown that in themselves they are clay or dust, mere matter, whose form is impressed upon them by society (The Ritual Process, 103).

Turner also notes that many of these ordeals have a linguistic character. One example from the Cheifmaking ritual of the Ndembu people is called the “Kukmukinddyila, which means literally ‘to speak evil or insulting words against him’; we might call this rite ‘The Reviling of the Chief-Elect’” (ibid, 100). During this phase of the ritual, the members of the Ndembu tribe gather around their chieftain-to-be and insult him. Anyone, whether man, woman, or child, may air their grievances against him in public “going into as much detail as he desires” (ibid, 101). Not only does this have a cathartic effect for the community, allowing for any private resentment to be practically addressed, but many tribes like this believe their words have magical potential, aiding in the change from one state to another. Turner writes that “In tribal societies, too, speech is not merely communion but also power and wisdom. The wisdom (mana) that is imparted in sacred liminality is not just an aggregation of words and sentences; it has ontological value, it refashions the very being of the neophyte” (Ibid, 103).

Much of the action in Virginia Woolf resembles this liminal process, especially its focus on language. From the very opening, when George and Martha begin their verbal sparring, we are caught watching the process of two people attempting to destroy each other through words. When Honey and Nick enter, the process only intensifies. George, who attacks and is attacked on two fronts, both by his wife and his new colleague, treats these conflicts as games. However, the way that “get the guests,” and “bringing up baby” progress reveal a purposeful intent. They are deliberately designed to wound by revealing and ridiculing the participant’s greatest secrets and fears. By the end of the night, the fun and games have lost their extemporaneous feel, moving from the realistic exchange of insults to a contest whose participants deliberately test each other’s mettle:

George

(Grabbing her hair, pulling her head back)

Now, you listen to me, Martha; You’ve had quite an evening… quite a night for yourself, and you can’t just cut it off whenever you’ve got enough blood in your mouth. We are going on, and I’m going to have at you, and it is going to make your performance tonight look like an Easter pageant. Now I want to get yourself a little alert. (Slaps her lightly with his free hand) I want a little life in you, baby. (Again)

Martha (Struggling)

Stop it!

George

(Again) Pull yourself together! (Again) I want you on your feet and struggling, sweetheart, because I’m going to knock you around, and I want you to be up for it. (Again; he pulls away, releases her; she rises)

[…]

Good for you, girl; now, we’re going to play this one to the death (Virginia Woolf, 212-213).

The goal here is the total destruction of the ego or, as George says “peeling labels,” and by the time the process is complete, he has destroyed the thing that both he and his wife care about most: the fantasy of a normal, happy life with the child they will never have. (Virginia Woolf, 95) Through their words, George and Martha reduce each other to nothing, a staccato of exhausted syllables exchanged before disappearing up the stairs into obscurity.

Nick and Honey, while not as dramatically affected by the liminal process, are not exempt from it. Nick, whose only concern is status, begins the play riding the wave of the future. A success in athletics and academics, he has even chosen a field that society values in the extreme: biology. However, by the end of the play, these youthful pretentions have turned to nothing and Nick, both a flop and a houseboy, is relegated to the margins of power. Honey, who is perhaps the play’s weakest character, offers up even less resistance. Unable to stomach conflict, she collapses into herself after George reveals her infertility, and does not recover until the night’s final moments. In fact, all of the characters, when they have reached the last dregs of their energy, seem to find rest in a place where they emerge equalized through the destruction of their personal myths. It is as if, tempered to their essence, they no longer have the time or energy for the artificial posturing of status. As is the goal of the liminal phase, what remains is the husk: who they “truly” are.

Considering the symbolism commonly associated with liminality also strengthens the link between Virginia Woolf and the rite of passage. According to Turner, because liminal entities exist outside of traditionally assigned social norms, they are often associated with the indeterminate or unknown. Often, extremely structured tribal societies regard those with liminal qualities as dangerous. In liminality, an individual changes into an outsider, treated in the same way the population of a wealthy suburb might regard a homeless man shuffling through a well-groomed front lawn. And, like the homeless and other outcasts which we have no real place for, these threshold people are deeply embedded into societal imagination. “As such, their ambiguous and indeterminate attributes are expressed by a rich variety of symbols in the many societies that ritualize social and cultural transitions. Thus, liminality is frequently likened to death, to being in the womb, to invisibility, to darkness, to bisexuality, to the wilderness, and to an eclipse of the sun or moon” (The Ritual Process, 95). These people vibrate when others remain static. Like Schrödinger’s much-cited cat, normative society can never quite be sure what they will do. Open up the box and they may be gone.

Symbolically, Albee’s characters accumulate symbolic relativity as the play progresses. While each begins the night in a fixed social state, these roles soon fracture. Characters who we believe earlier hate each other show that they are deeply in love. Each person plays multiple, often contradicting parts, changing attitudes as we would change clothes. Honey, with her hysterical pregnancy, vacillates between mother, maiden, and child. Unable to face up to reality, she hides in the bathroom while another woman seduces her husband, frequently regressing into her own childishness. Throughout the play she continues to waver in and out of focus; in one version of the play she willfully forgets the entire night (Virginia Woolf, 211). Encapsulated in the symbol of aborted birth, she, like her child, is caught between being born and living. Constantly vomiting, she balks at her own existence as if poisoned by it, her love of brandy and its obvious deleterious effects reflective of a general attitude toward life, one that accepts what it hates with cloying sweetness and kills it once it passes beyond the threshold of the skin.

Nick likewise takes part in a network of symbols, also having to do with interrupted virility. Strong, potent, the closest the play has to the traditional alpha male, Nick seems destined to shoot up in the ranks like a rocket, but he is unable to consummate the affair that would ultimately launch his career. George, who knows the ins and outs of the University of New Carthage better than most, is half serious when he says that “You can take over all the courses you want to, and get as much of the young elite together in the gymnasium as you like, but until you start plowing pertinent wives, you aren’t really working” (Virginia Woolf, 113). Thus, when Martha declares that Nick is a “flop”, the play echoes with more than just a dirty joke. His ultimately unsatisfying attempts to achieve intercourse signify his flaccid potential. The limp penis, deprived of its usefulness, reveals that he, like George, has trapped himself in new Carthage. A climber without any true ability to climb, Nick finds himself two rungs off the floor, unable to move another foot above or below.

It is more difficult to show specific examples with George and Martha, not because of any lack of liminal symbolism, but because their lives overflow with it. Already partial outsiders due to their inability to live up to society’s expectations, their liminal status has even rubbed off onto their home. According to Richard Schneider, the set in the first production was not meant to be realistic in the strong sense. “It has all kinds of angles and planes that you wouldn’t ordinarily have, and strong distortions. Edward [Albee] wanted the image of a womb or a cave, some confinement” (Schechter, 72). This serves to compress the action, but in liminality symbols like this have an additional purpose. The womb contains particularly strong resonances with the liminal phase, signaling to both participants and any potential audience that a change will soon occur: that this is a place where something will soon be born.

George and Martha’s relationship, too, has a liminal quality. While Nick and Honey seem content to ignore each other, the leading couple can never seem to tell whether they love or hate each other: Even among the bloodshed we find moments of surprising intimacy. After a frustrated George pulls out a toy shotgun and scares most of the room half to death by “firing” it at Martha, she reacts not with anger, but with lust (Virginia Woolf, 57-59). This gives the impression that, despite their marital problems, the two have a deep and abiding affection for each other. In a series of speeches in the third act, Martha expresses the ambiguity of their relationship most clearly. For her, George is the only man she has ever loved, but who she cannot love completely, the one “Who can hold me at night so that it’s warm, and whom I will bite so there’s blood […] Who has made the hideous, the hurting, the insulting mistake of loving me and must be punished for it” (Virginia Woolf, 191). Suspended between two points, they have no recourse but to hit out at each other until they hear the sound of something snap.

The way that Albee’s characters use language also exudes a kind of symbolism, one which muddies the truth, elevating liminality to epistemic status. George and Martha, for example, are constantly telling stories, some of them verifiable, some of them not. When George tells Nick the story about the boy who killed his mother and father and Martha later reveals that the boy was him, the audience generally trusts she is telling the truth because of George’s reaction (Virginia Woolf, 84). Truth in the world of Virginia Woolf is the most pointed weapon. However, by the end of the play, it becomes more and more difficult to tell what is true and what is fabrication. In the third act, George and Martha even argue about the placement of the moon, whether it is down or up (Virginia Woolf, 197-201). When George waxes tangential about a time when he went for a cruise in the Mediterranean with his parents, we can reasonably assume that it never happened because it does not fit with an earlier timeline. However, because of the constant storytelling, truth seems to slip through our fingers, putting everything we have been told into doubt retroactively. Perhaps George did not kill his parents after all. Perhaps, in this world, the moon can set and rise again in the same night. In this way the characters, especially George, cast their linguistic spell over the theatre. Who they actually are, what their background is, even the theatrical illusion itself, hangs tenuously before us, like a mirage. These characters could be anyone, and like Martha and George’s child, bear the potential of being destroyed with a twist of the narrative.

Finally, Virginia Woolf resembles the liminal phase of a rite of passage in its final effect on its participants. Aside from symbolically destroying their social identity, Turner writes that the liminal process often produces the feeling of “an essential and generic bond, without which there would be no society” between participants (Turner, 97). Turner connects this bond directly to the statelessness experience of liminality. If one neophyte was a king and the other a peasant, in liminality there is no difference between the two of them, opening an unprecedented relationship. According to Turner:

“It is as if there are two major “models” for human interrelatedness, juxtaposed and alternating. The first is of a society as a structured, differentiated, and often hierarchical system of politico-legal-economic positions with many types of evaluation, separating men in terms of “more” or “less”. The second, which emerges recognizably in the liminal period, is of a society as an unstructured or rudimentary structured and relatively undifferentiated comitatus, community, or even communion of equal individuals who submit together to the general authority of the ritual elders” (The Ritual Process, 96).

He later identifies this universal bond as “communitas.”

For Turner the concept of communitas is not merely a feeling of brother/sisterhood between unlike social beings. Because of its almost universal association with ritual and mystic feeling, he situates it at the crux of religious feeling itself. While religious figures often build structure and institutions to contain or reproduce communitas, spontaneous communitas need not necessarily occur within a religious context. Spontaneous or existential communitas, which Turner contrasts to Normative and Ideological communitas, exemplifies the emotive and intuitive within the spiritual experience (The Ritual Process, 132). It is the core around which religious structure is based “almost everywhere held to be sacred or “holy,” possibly because it transgresses or dissolves the norms that govern structured and institutionalized relationships and is accompanied by experiences of unprecedented potency”(The Ritual Process, 128).

If Albee stages the liminal in Virginia Woolf, then in its climax he presents us with a reversal from antagonism to empathy in the occurrence of communitas. The summoning and sacrifice of George and Martha’s imaginary child, “Sonny Jim”, displays all of the hallmarks of the liminal phase: its indeterminacy, its statelessness. However, because it is at the apex of the performance, the characters take the liminal process to its extreme. With Honey and Nick as an audience, George forces Martha to re-invent their son’s childhood. The social nature of this act seems to have something to do with what happens next. It is as if by telling others about Sonny Jim, George and Martha give the myth an aspect of reality, giving them false status that producing an heir would open them to. To use Turner’s terminology, they begin to slide into a more socially acceptable “state” through which they might participate in the larger community. The obvious joy that the idea of having a child gives the couple makes what George does next that much more painful. By informing Martha of Sonny Jim’s death, he utterly destroys the illusion of a happy future and symbolically crushes the fantastical past. As so many other critics have noted, this seems to be Martha’s last hope. After this illusion crumbles, the cast collapses into exhaustion, a cathartic release that sees the leading couple climbing the stairs into an unknown future. As Gerald Weals suggests, we do not actually know what happens after the lights fade on Martha and George. Possible endings are multiplex, from the idea that “the death of their child may not be the end of illusion but an indication that the players have to go back to GO and start again their painful trip to home,” to one where “the truth- as in The Iceman Cometh– brings not freedom but death” (22). However, what does seem to be clear is that this is in the final phase on the stop to complete liminality. Scoured to their marrow, Martha and George have nothing but their bare essences and each other. The vessels of status broken, they flow indiscriminately between each other, all opposition evaporating in the light of the morning.

It is in this final hour, when our characters are at last reduced to nothing, where we also find communitas. George and Martha, normally two egos that grind up against one another in a contest of who can wear the other down more quickly, operate as one, helping one another to their bedroom with an uncommon tenderness. Honey and Nick, who have been brought into the liminal phase purely because of their proximity to Martha and George, are also caught in this feeling of communion. For Honey, the religious connotation inherent in the word is quite literal. The product of a religious background herself, she shows her empathetic connection by joining in with George’s recitation of the requiem mass:

GEORGE

Requiem aeternam dona eis, Domine.

HONEY

Et lux perpetua luceat eis (Virginia Woolf, 237).

Nick’s reaction comes in a characteristically less muted manner. Weales notes his “broken attempt to sympathize,” as if his inability in the last moments of the play to say anything meaningful indicates that he cannot understand what George and Martha are really going through (21). Yet his violent outcry just pages before, “JESUS CHRIST I THINK I UNDERSTAND THIS!” seems to show that, for at least a brief moment he and George are one in identification (Virginia Woolf, 236). The creation of Sonny Jim is perhaps a parallel to his own longing, and in his death a pain that most parents would feel. Thus, when he stutters out “I’d like to…” but is unable to finish, it does not show his inability to empathize but the depth of his feeling (Virginia Woolf, 238). Unable to find words to describe these powerful emotions, he lapses into silence, speaking with emptiness more than words could adequately express.

The climax of Virginia Woolf also reveals an instance communitas in the way that it cites religion. As I have mentioned before, for Turner, religion is the institutionalization of communitas which he identifies as normative and ideological. He writes:

“Ideological communitas is at once an attempt to describe the external and visible effects- the outward form, it might be said- of an inward experience of existential communitas, and spell out the optimal social conditions under which such experiences might be expected to flourish and multiply. Both normative and ideological communitas are already within the domain of structure, and it is the fate of all spontaneous communitas in history to undergo what most people see as a “decline and fall” into structure and law” (The Ritual Process, 132).

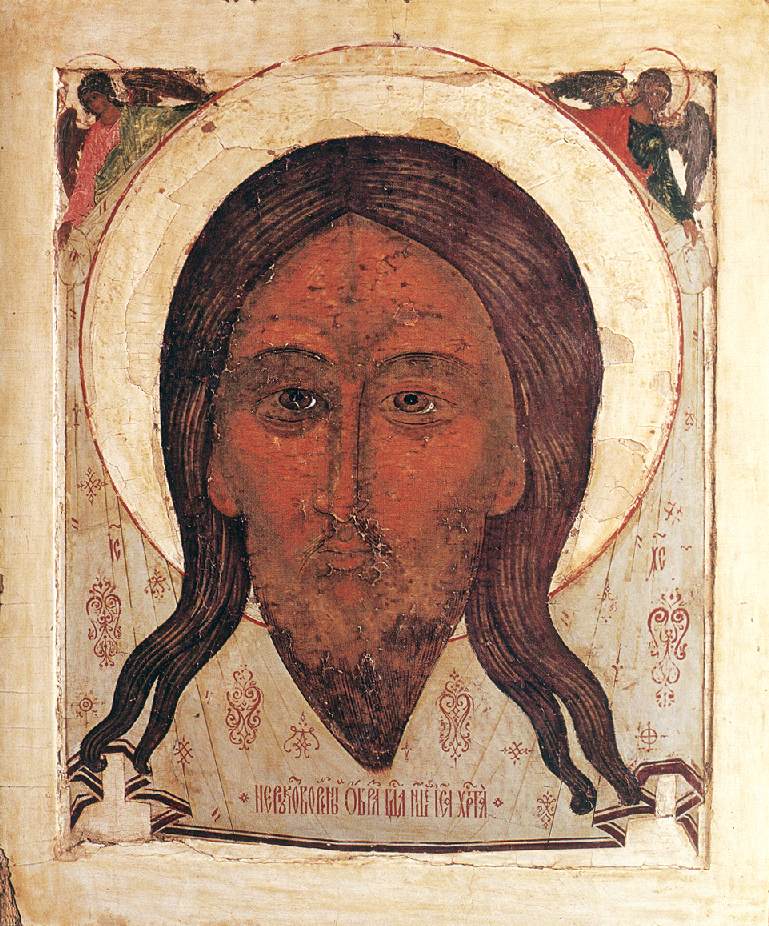

Institutionalized religion and its rituals, like the Requiem mass, are the container through which believers store mystical feeling. However, though he does cite Catholic ritual, it seems clear to me that George does not intend to reproduce anything having to do with Christianity. The ending of Virginia Woolf seems too spontaneous, too emotionally taxing on its participants to have anything to do with an ideological structure. Rather, this is a citation or symbol intended to reach its audience at a subconscious level. The characters in Virginia Woolf go through an emotional scouring that leaves them clean, much more clearly an example of existential communitas than the potentially empty motions of a two thousand year old practice. Instead, the mass seems to be an outward sign of an inner feeling, an eruption of Paolucci’s “religious awe” into the mundane world (62).

Of course, Virginia Woolf does not work perfectly as a rite of passage, nor is the rite of passage a foolproof model. Jenny Hockey writes that “it is important to see rites of passage as a flexible, working model or schema, geared towards making sense of diverse, empirical material”, but if a model encompasses everything it loses its effectiveness (231). Taken to the most extreme form of abstraction, one could apply the three step process contained in Van Gennep’s Rites of Passage to nearly any event where change occurs, as it is essentially a modified version of Hegel’s dialectic: separation, transition, and incorporation are analogous to thesis, antithesis, and synthesis. Virginia Woolf resembles a rite of passage but that does not mean it is one. One could also quite simply say that Albee’s characters change, as is the case in nearly every dramatic work. This leads me to a farther point: While it is clear that George, Martha, Nick, and Honey undergo an emotional catharsis at the end of the play, this is not the same as a passage between two ontological states. Characters might feel a change occurring in themselves, but without the ritual worldview, where who a person is may be literally changed by the actions of another, the effect is simply not the same. For the efficacy of my argument, one must take on the assumption that, in the world that Albee has created for us, spontaneous ritual is possible, and that it works. This is the interpretation’s first principle and its Achilles heel, and it either stands or falls on my audience’s willingness to accept an imaginative leap.

However, despite these difficulties, interpreting Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? as the staging of a ritual rite of passage does solve some problems which critics have with Albee’s work. For many early commentators, the play’s ending was of particular difficulty. Clurman notes that “the end of his play- which seeks to introduce “hope” by suggesting that if his people should rid themselves of illusion (More exactly, falsity) they might achieve ripeness- is unconvincing in view of what has proceeded it” (78). Weales feels likewise unconvinced, questioning the truth and illusion dichotomy as Albee presents it, calling it a cliché in the tradition of William Inge’s The Dark at the Top of the Stairs. His question, “How can a relationship like that of Martha and George, built so consistently on illusion (the playing of games), be expected to have gained something from a sudden admission of truth?” seems particularly pointed assuming a realistic idiom(31). The almost magical transition between a failing relationship and one that is once again whole seems disingenuous considering what the audience knows of the couple. This may also be behind Richard Schechter’s now infamous editorial in the Tulane Drama Revue entitled “Who’s Afraid of Edward Albee”, where he trumpets the play as an example of all that is wrong with American Drama, calling it and the man who wrote it “phonies.”

“Albee is not conscious of his own phoniness, nor the phoniness of his work. But he has posed so long that his pose has become part of the fabric of his creative life; he is his own lie. If Virginia Woolf is a tragedy it is of that unique kind rarely seen: a tragedy which transcends itself, a tragedy which is bad theatre, bad literature, bad taste— but which believes its own lies with such conviction that it indicts the society which creates it and accepts it. Virginia Woolf is a ludicrous play; but the joke is on all of us ” (63-64).

This seems to be a particular paradox that critics find in Virginia Woolf: it seems that if the characters are genuine it’s message must not be, and if it’s message is genuine, then it’s character seem false, despite, or perhaps because of, it’s technical brilliance.

By framing the play as a ritual rite of passage, Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? can remain as it is without seeming disingenuous. Its ending becomes a literal instance of magic, the transformation of four characters from one state into another. The way Martha and George relativize truth changes from a rallying cry of the postmodern into an attribute of the liminal phase. For, while Virginia Woolf does have a great deal to say about authenticity, truth and illusion are such broad categories that nearly every literary work touches on them in some way. Self-deception has been a trope within the dramatic form since Oedipus. Tennessee Williams’ plays all contain at least one character is living their life in a dream that they have cocooned themselves in, and these unrealistic dreams usually lead to their downfall. People who convince themselves of half-truths are so common in life that if an author excluded them they would have no one to write about. If truth and illusion are all Virginia Woolf is about, then the play only represents an extraordinarily skilled way of giving the same tired message that tragic writers have always written. In this sense, not only would the play’s message seem false, but unoriginal.

Beyond solving these problems of interpretation, framing the play as a ritual rite of passage opens up alternate staging possibilities for a play whose productions are tragically standardized. One could imagine certain aspects of the play enhanced or emphasized in order to make its ritualized action more visible. The goal of criticism, after all, is not to explain away literature, but to make it more visible to its audience in as many ways as it can. Albee’s play is imperfect as all writing is, but Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? represents a masterful example of the playwright’s craft. Whether because of its dense symbolism, its language, or its sharply drawn characters, Virginia Woolf scintillates even now. It is a play that deserves the same brilliance in staging and analysis that it was written with, to be broken into and freed, liquid and wriggling, into a static world.

Clurman, Harold. “Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf?” In Edward Albee: A Collection of Critical Essays, edited by C.W.E. Bigsby, Prentice-Hall, 1975 (76-79).

Albee, Edward. Stretching My Mind. Carol and Graff, 2005.

Albee, Edward. Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? 1978. Atheneum, 1962.

Paolucci, Anne. From Tension to Tonic: The Plays of Edward Albee. Southern Illinois University Press, 1972.

Esslin, Martin. “The Theatre of the Absurd: Edward Albee.” In Edward Albee: A Collection of Critical Essays, edited by C.W.E. Bigsby, Prentice-Hall, 1975 (23-25).

Gennap, Arnold Van. Rites of Passage. Translated by Monika B. Vizedom and Gabrielle L. Caffee, University of Chicago Press, 1960.

Weals, Gerald. “Edward Albee: Don’t Make Waves” in Modern American Drama, edited by Harold Bloom, Chelsea House Publishers, 2005 (21-44).

Hockey, Jenny. “The importance of being Intuitive: Arnold Van Gennep’s The Rites of Passage.” In Mortality, Volume 7 Issue 2, July 2002 (210-217).

Horn, Barbara Lee. Edward Albee: A Research and Production Sourcebook. Praeger, 2003.

Schecter, Richard. “Reality Is Not Enough: An Interview with Alan Schneider”. In Edward Albee: A Collection of Critical Essays, edited by C.W.E. Bigsby, Prentice-Hall, 1975 (69-75).

Schechter, Richard. “Who’s Afraid of Edward Albee?” In Edward Albee: A Collection of Critical Essays, edited by C.W.E. Bigsby, Prentice-Hall, 1975 (62-65).

Turner, Victor. From Ritual to Theatre: The Human Seriousness of Play. Performing Arts Journal Publications, 1982.

Turner, Victor. The Ritual Process: Structure and Anti-Structure. 2nd Edition, AldineTransaction, 2008.