The fact that experimental art calcifies into sameness should not come as a surprise, since it is the general trend of art in general since the enlightenment. Ever since art and utility became separated and art for the sake of art became the norm, it has gained a magical quality that separates it from its processes and the experience of the people who create it. the American philosopher John Dewey, in his 1934 book Art as Experience, puts it better than I ever could when he writes, “When artistic objects are separated from both conditions of origin and operation in experience, a wall is built around them that renders almost opaque their general significance, with which esthetic theory deals. Art is remitted to a separate realm, where it is cut off from that association with the materials and aims of every other form of human effort, undergoing, and achievement.”

Put another way, when a piece of art is put into a museum, a poet made national laureate, or a piece of literature is taught in high-school English, it becomes a holy relic that we either reverie or despise because we sense it may not actually be a piece of the true cross. And, like many relics, true origin matters very little. Its presence in the church has made it holy.

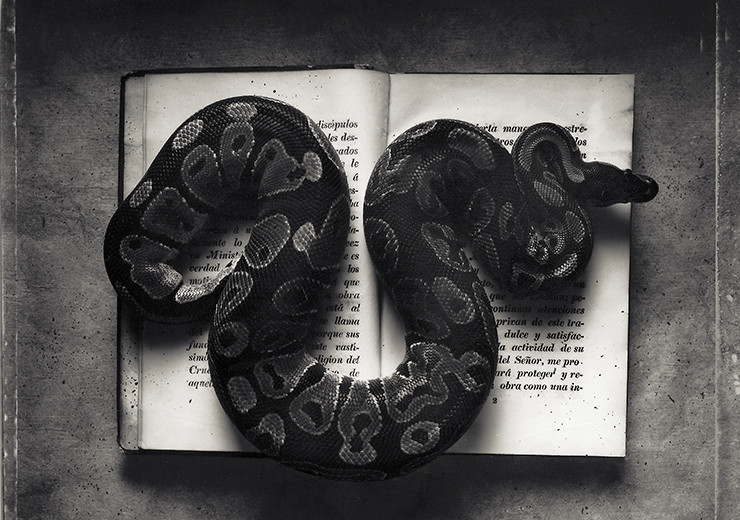

New forms of experimental art often represent an attempt to escape this artistic canonization, while containing within them the seeds of their own failure. Take, for example, Marcel Duchamp’s Fountain, where the artist famously submitted a urinal signed “R. Mutt” for display at the inaugural exhibition of the society of independent artists in 1917. The piece intentionally subverted the idea of fine art, both degrading the stuffy gallery culture of the time and elevating everyday objects. Art, Duchamp asserted, is what we perceive as art. It is defined by its arbitrary presence in a building designed for art.

Instead of deconstructing the museum, however, Duchamp only added to what museums would consider displaying. The museum itself canonized the radical gesture of diverting from gallery culture, making it just as inaccessible to everyday people as any rare Rembrandt, perhaps more so, since to understand Fountain, a person needs to be well versed in the artistic climate of the early 1900’s. That which a person cannot understand, but which is held in esteem by experts, increases its mystery and therefore its status as art. We begin to identify art as something defined by its lack of comprehensibility. By protesting arts elevated place, Duchamp contributed to art’s continued elevation.

By slow degrees, experimental art as a genre became, at least in the eyes of experimental artists, the holy of holy’s, not just the fingerbone of a hallowed saint, but the saint himself, reclothed in flesh and handing out miracles. It separated itself even farther from a thing which, by its very nature, already seems separate. Caught in its own self-referential cycle, it forgets where it comes from entirely, its raison de entre to perpetuate its own inscrutable position. The only way to free experimental art from its self-imposed exile is to remind its makers that, as Dewey writes, “Mountain peaks do not float unsupported; they do not even just rest upon the earth. They are the earth, in one of its manifest operations.”